One piece of big news this month has been the new estimates of the effects of Obamacare on employment.*

The old estimates had shown that employment was going to go down by just under 1 million people. The new estimates showed it would go down by about 2.5 million. That’s going from a 0.6% reduction in employment to a 1.5% reduction.

Both estimates came from the CBO (Congressional Budget Office). The CBO is generally viewed as non-partisan by both parties.†

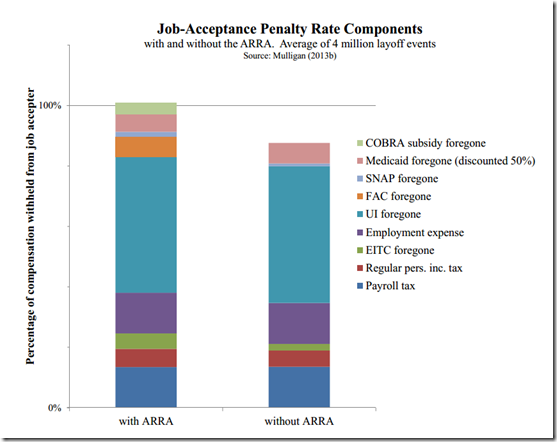

What did happen this time around is that the CBO updated their methods, largely based on the influential work of Casey Mulligan. In particular, Mulligan researched the tax disincentives for employment under the Act. Specifically, the lower your cash income, the higher the proportion of healthcare benefits in your compensation package. Those healthcare benefits are, in turn, “means-tested”. I know this sounds kludgy, but “means-tested” means that as your income goes up, you start to get charged for the free parts, essentially paying a tax that wasn’t there before. Fifty years ago, prominent Democratically-aligned economists recognized that means-testing was problematic. Mulligan provides this quote:

… James Tobin, a John F. Kennedy adviser, Nobel laureate and leading Keynesian economist of his day, said in a 1965 article, a 100 percent tax rate causes “needless waste and demoralization,” adding:

This application of the means test is bad economics as well as bad sociology. It is almost as if our present programs of public assistance had been consciously contrived to perpetuate the conditions they are supposed to alleviate.

And, let me stick my neck out here and generalize: means-testing is the fault of Republicans. Instead of making principled (but politically unpopular) stands against welfare programs through the years, they’ve instead consistently settled for (economically ludicrous) bean counting.

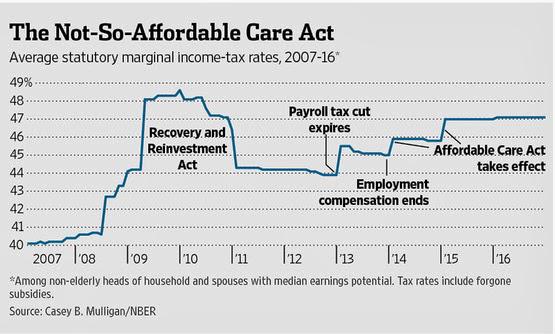

Here’s Mulligan’s estimates of marginal tax rates averaged across taxpayers:

Mulligan’s point is that Obamacare cranks up the average across taxpayers of the marginal tax rates each of them pays (the two steps on the right) mostly by increasing the marginal tax rates on people with lower incomes (through means-testing). Do note that the first of those steps just occurred, and the second one is still 10 months out, so the effects on employment have barely started. Mulligan thinks the CBO estimates are a big improvement, but that they’re half of the reduction he forecast in his earlier work.

Do note and emphasize the point made: means-testing makes Obamacare a healthcare benefit for many paired with a substantial increase in marginal tax rates on the incomes of the poor.

Fair enough. Now, take a step back and think about our labor and healthcare markets of, say, 10 years ago. There’s a lot of reasons to think that the way we paid for healthcare then was goofy (most employees receiving a benefit that could be more or less than they need because their employers get a tax break, with a fairly small minority left to their own devices) and in need of reform. Did this distort labor markets? Almost certainly the answer is yes. Now we’ve introduced a healthcare law that distorts labor markets in a different way. My point is that we can’t just say that the distortions are worse because they’re different, when in fact the situation may have improved along some dimensions So, both conservative and liberal views have some validity here (do note that John Cochrane, a much more important economist than me, and one who I usually agree with, stated that my view that it’s possible that the “effect of [earlier] government policy was to induce too many people to work is just silly.”).

The thing is, prior to passage supporters of Obamacare stated publicly that the act should be expected to increase employment.

Mulligan is actually pretty clear about this:

Why didn't they say, no, we didn't mean the labor market's going to get bigger. We mean it's going to get smaller in a good way …

His point is that supporters of Obamacare always argued casually that it would increase employment and that this was a good thing. Those supporters never examined deeply whether their supposition was correct. Now that deeper analysis has been done (by Mulligan) and confirmed (by the CBO), the supporters of Obamacare argue that it will decrease employment and that’s a good thing too.

Here’s Tyler Cowen writing at Marginal Revolution:

People, it is rather difficult to have it here both ways.

Cowen’s writing is usually very clear, but I found this post very confusing. Let me summarize. His position is that:

- Progressives have argued that the Great Recession was caused by a shift of aggregate demand to the left.

- The policy solution to that is something like the stimulus package of 2009, or the loose monetary policy of the last few years: both intended to shift aggregate demand back to the right.

- A policy solution is necessary because progressives/Keynesians assume people act irrationally on the aggregate supply side: when there’s a bad demand shock suppliers should reduce their (nominal) prices to maintain their (real) output. The progressive position is that suppliers of labor, in particular, have expectations that irrational in that they believe bad times won’t last and therefore don’t reduce their (nominal) wages quickly enough to avoid large scale (real) unemployment. These three points are Cowen’s one way.

- Cowen’s other way is that Obamacare supporters are now arguing that labor suppliers, in particular, are rational and will recognize that with Obamacare in place they can choose to spend their time in ways more fruitful than employment.

- So what Cowen is saying is that there’s a really big logical hurdle to clear if you’re going to use workers’ irrationality to justify one big progressive program, and workers’ rationality to justify the other big progressive program.

Another way to interpret these arguments is through the likely effect on the unemployment rate. Remember the goofy thing about official measurements of unemployment: you have to want a job enough to be actively looking in order to be counted. The position of liberals/progressives is that some people are going to shift from being employed to being out of the labor force rather than unemployed. If this is true, there won’t be much affect on the unemployment rate. For example, right now, the unemployment rate is roughly:

10/(140+10) = 6.7% (where everything is in millions of people)

After the ACA changes take effect, we will see something like this:

10/(137.5+10) = 6.8% (where everything is in millions of people)

On that basis, it looks like no big deal. I predict that this argument will be used in the major media over the next two years.

Alternatively, the conservative position is that what really counts is that right now 140 million people are doing the production that supports the other 170 million (a ratio of 1 to 1.21). After the ACA changes take effect, it will be 137.5 million doing the work for 172.5 million (a ratio of 1 to 1.25). That’s 3% more work for the workers.

You might think that this is OK because those 137.5 million will be getting paid more because they have to be more productive. Here’s Princeton economist, and former Vice-Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Blinder making exactly that point. Greg Mankiw shows that this is naive. His argument is one that we’re going to start this month, and work on through the rest of the semester. In short, this sort of policy change is going to cause a permanent decline in the level of real GDP. This will be proportional to the decline in employment, so wages will remain unchanged.

John Cochrane also brings an important point to bear on the problem. My wife has a wry joke for people who complain about not liking their jobs: that’s why they pay you. If you liked it, you’d do it as a hobby. Here’s Cochrane:

Hey, work isn't fun. We do it for the money. If not for the money, for the health insurance. Sure, it would be great if the government would cover my health insurance, my food, gas, and housing, so I could devote myself full time to glider flying.

Think about that. Why exactly are we worried about job-lock for healthcare, when most of us are already in a state of employment-lock for food, shelter, transportation, entertainment, education, and so on? The only difference is that for those items we’re locked to having a generic job, while with healthcare we’re locked to a specific job. Perhaps the specificity is the problem we should have been addressing all along. Do you think anyone in Washington seriously considered whether they could address that specificity without putting 2.5 million people in the position of finding it beneficial to choose leisure over employment?

In the end, there isn’t a solid answer here. Instead, we’re comparing before and after when the features are jumbled. Before, we worked more hours, got more real GDP, but got less healthcare and less leisure. After, we’ll work less hours, get less real GDP, but get more healthcare and more leisure. On average. The true problem here is distributional: some people think the before scenario will still apply to them, and that the after scenario will apply to someone else. That’s a big problem.

FWIW: Craig Newmark offers the following point about the liberal/progressive position:

I love that Liberals have now decided that what individuals voluntarily choose--regardless of the consequences for the rest of us--is fine. Question for them: shouldn't we therefore allow individuals to choose whether or not to have health insurance and if so, what kind?

* Obamacare is the name of convenience. The short name for the law is the Affordable Care Act, so you will see ACA used quite a bit.

† The big problem with the CBO is that they evaluate the economics of laws as they are written by Congress, not how they are put into practice by the executive branch or later modified by Congress. It’s become standard practice in Washington to include items in laws to game the CBO estimates that are later reneged upon (that isn’t what’s happened in this case, but it is a concern with Obama’s executive orders changing the requirements under the Act).