Assessing income inequality is a hornet’s nest for those who are weak at statistics.

First off, most of the data we have is averages, which can’t tell us anything about inequality.

Secondly, many people slip mindlessly between the concepts of absolute and relative poverty. The latter is having less than others, while the former is not having enough.

Relative poverty exists everywhere, and is what is important if you think that income inequality is a problem.

Essentially, absolute poverty no longer exists in developed countries. Yet when we worry about others “not having enough” this is the only kind of poverty measure that’s important.

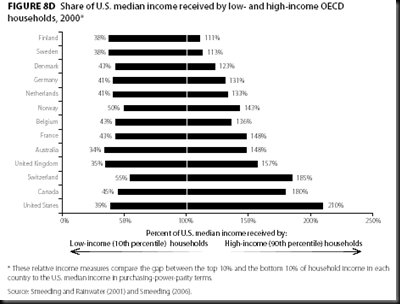

Tim Worstall, writing for the Adam Smith Instituted, reprinted this chart that can clarify matters:

The bars show different countries. The data is on net income after taxes have been removed and benefits added back in, adjusted for international prices using PPP.

The endpoints of each bar show the income of the 10th percentile and 90th percentile in each country. So, it’s not the poorest (who are probably close to zero everywhere) or the richest (who are off the chart to the right). Having said that, the most expansive view of the “middle class” usually runs from the 20th to the 80th percentile, so this is getting us that plus the richest half of the poor on the low end and the poorer half of the rich on the top end. What’s key is that this isn’t showing averages.

And what does it show?

- America has the most unequal distribution of income of the countries shown.

- America’s poor are no poorer than the poor in other countries.

- America’s rich are richer than the rich in other countries.

If you put these together it means that our inequality is not a result of our poor being worse off, but of our rich being better off.

And yet the world is fill of people who think America is somehow a bad place because of our inequality.

This is pretty dumb. An example may help:

- The poor in countries A and B both eat only turnips.

- The rich in country A eat a variety of fresh vegetables.

- The rich in country B eat a variety of canned vegetables.

Would any rational person claim that people in country B are better than those in country A? To do so, you’d need to believe that people shouldn’t eat what’s best, but rather what’s closest to what their neighbors eat.

But that’s just silly … because it would mean you judge the wellness of your community by trying to match the contents of your grocery cart to that of the other people in the checkout line.

No one does that in real life. And yet the chart tells us that this is what people who are concerned about inequality in America think we should do.